The urethra in males is the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body and also serves as the channel though which semen is ejaculated. The anterior urethra is the portion of the urethra from the tip of the penis to just before the prostate. The posterior urethra is the part of the urethra that travels through the prostate and the external sphincter valve.

An anterior urethral stricture is a scar of the urethral epithelium (the urethra’s outside layer of cells) and commonly extends into the underlying corpus spongiosum (a column of erectile tissue that surrounds the urethra). The scar (stricture) is composed of dense collagen and fibroblasts (proteins that form cell-producing connective tissue) and thus contracts in all directions, shortening urethral length and narrowing the diameter of the urethra. Strictures usually do not cause symptoms until the urethra tube is below a certain size.

Anatomy

- The relative location of the urethra within the spongiosum changes along the divisions of the urethra. The anatomic location of the lumen (urethral cavity) in relation to the spongiosum is critical for selecting the sites for internal surgical incision in the urethra.

Anterior Urethral Strictures

Causes

- Most present day urethral strictures are the result of blunt trauma to the perineum (the area between the thighs from the end of the spinal column to the pubic bone), such as straddle injury, or instrumentation, such as traumatic catheter placement or removal or a chronic indwelling Foley catheter.

- Inflammatory strictures, such as those secondary to gonococcal or chlamydial urethritis (inflammation of the urethra caused by gonococcal or chlamydial bacteria), are relatively uncommon today. In impoverished countries, more than 90 percent of strictures are inflammatory. In Western countries today, the most common cause of inflammatory strictures is lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA), where whitish plaques commonly affect the glans (the head of the penis), meatus (urinary opening) and foreskin. It is a common cause of phimosis (infection of the foreskin), and thus often occurs temporarily after circumcision. LSA starts as inflammation of the glans that can result in severe narrowing of the urethral opening, high pressure voiding and eventual inflammation of the (Littre) glands in the tissue surrounding the urethra. Potentially, extensive urethral stricture disease can occur in this manner.

Physical Exam: Signs and Symptoms

- As the urethral lumen (cavity) gradually narrows, obstructive voiding symptoms worsen, and this becomes an insidious pattern. Symptoms include weak urinary stream, straining to urinate, a spread-out stream, hesitancy, incomplete emptying, urinary retention and post-urination dribbling. Frequent and painful urination are also common initial complaints.

- Narrowing of the urinary opening results in a deviated or spread-out urinary stream.

- To touch, the urethra often reveals firm areas consistent with spongiofibrosis (scar tissue of the corpus spongiosum, which surrounds the urethra). A tender mass along the urethra is usually an abscess (pocket of infection or pus).

- Urinary peak flow rates less than 10 milliliters/second indicate significant stricture (obstruction/blockage).

- Urinalysis is done to assess for urinary tract infection.

Other Diseases with Similar Symptoms

- Bladder outlet obstruction from an enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia).

- Bladder neck contracture after endoscopic prostate surgery (TURP) or after a simple or radical prostatectomy (removal of the prostate).

- Urethral cancer – biopsy needed for diagnosis.

- Urethral polyp.

Stricture Evaluation

- Retrograde urethrography (RUG) and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) dynamic contrast imaging is the best approach despite the advent of newer imaging methods. Both studies commonly are needed to fully assess stricture length, location, caliber and the functional significance of the stricture.

- Ultrasonography is particularly useful for bulbar urethral stricture evaluation (the bulbar urethra begins at the root of the penis and ends at the urogenital diaphragm, which supports the prostate). The advantage of using sonography is that true stricture length can be determined before the operation, and thus graft or flap mobilization can be performed first with the patient on his back. Thus, patient time in surgery and positioning complications are limited.

- With the use of a pediatric cystoscope (an endoscope for inspecting the urethra and bladder) or flexible ureteroscope (a very narrow, yet long, endoscope), the degree of urethral lumen (cavity) elasticity and inflammation can be assessed. This is useful for confirming or clarifying urethrography (X-ray) findings and can visually assess urethral mucosa and associated scarring.

- Calibration (bougie-a-boule) – serial metal instruments that are used to determine the caliber or size of the urethra.

Complications of Urethral Strictures

Complications of stricture disease are:

- urethral discharge

- urinary tract infection

- cystitis (inflammation of the bladder)

- chronic prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate gland) or epididymitis (inflammation of the epididymis, a system of ducts that stores the sperm during maturation).

- abscess in tissue surrounding the urethra

- urethral diverticulum (abnormal pouch opening from the urethra)/calculus (hardened mineral salts)urethrocutaneous fistula (abnormal passage)

- urethral cancer (one third to one half of males with urethral cancer have a history of stricture disease).

- bladder stones (due to chronic slowing or stopping of urinary flow and infection).

Treatment Options

The goal of stricture management is cure and not just temporary management. Open surgical urethroplasty (scar excision surgery) has a long-term success rate of roughly 90-95% and should be considered the gold standard on which all other methods are judged.

Stricture management techniques are:

- urethral dilatation

- internal urethrotomy (surgical incision into the urethra for relief of stricture)

- excison of the scar and primary anastomosis (end-to-end anastomosis of tissue)

- free graft (skin, mucosal lining of cheeks, outer layer of bladder)

- island flap of penile skin or of foreskin

- scrotal island flap

- combined tissue transfer (combination of the above techniques)

Urethral Dilatation

- By and large, dilatation is only a management tool and not a cure. This is usually reserved for patients who are not candidates for more aggressive surgical intervention.

- The least traumatic and safest methods are serial catheter dilatation over several weeks or balloon dilatation.

- Dilatation potentially cures only pure epithelial strictures with minimal to no spongiofibrosis.

- To be effective, the scar needs to be stretched without causing more scarring. The best chance for this is to stretch the scar without causing bleeding. Bleeding from the urethra means that the scar was torn and the stricture will soon recur and result in worsened stricture length and density.

- Overall, long-term success is poor and recurrence rates high. Once interval dilatation is discontinued, the stricture will recur.

Internal Urethrotomy

- Internal urethrotomy (surgical incision into the urethra for relief of stricture) encompasses all methods of transurethral incision or ablation to open a stricture.

- The goal of cutting a stricture is to have epithelial regrowth before scar recurs in the same area. At best, the result of urethrotomy is to create a larger caliber stricture that does not obstruct urination.

- Urethrotomy is potentially curative for short strictures (less than 1 cm) that have minimal spongiofibrosis.

- After each successive urethrotomy, there is a period of fleeting good urinary flow, followed by a worsened degree of spongiofibrosis and lingering stricture. There are also reports of lumen (cavity) obliteration, as well as hemorrhage (heavy bleeding), sepsis (a serious, body-wide reaction to infection), incontinence, erectile dysfunction, glans numbness and abnormal erection caused by disease rather than sexual desire.

- In the short-term (less than 6 months), success rates are 70 to 80 percent. After one year, however, recurrence rates approach 50 to 60 percent and by five years, recurrence falls in the range of 74 to 86 percent (depending on stricture length and degree of spongiofibrosis).

- Attempts to improve the mediocre long-term results of internal urethrotomy have been made with laser urethrotomy. Contact mode Nd:Yag lasers have been used to “chisel” out the scar. However, results are not superior to standard techniques.

Urethroplasty

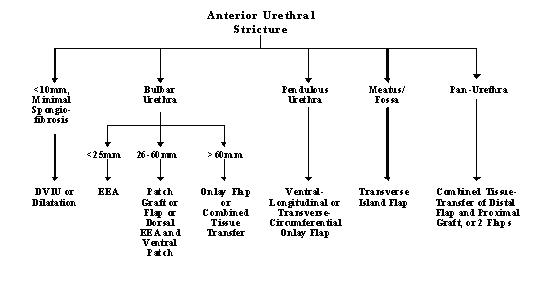

Urethroplasty is scar revision surgery. Before any urethroplasty, the scar should be stable and no longer contracting. Thus, it is preferred that the urethra not be instrumented for three months before planned surgery. If the stricture patient goes into urinary retention, a suprapubic tube should be placed. General guidelines for management are detailed in Figure 1.

Excision and Primary Anastomosis (EPA)

- Excision of the complete scar and primary anastomosis (coalescing blood vessels) is the optimal stricture repair.

- EPA is appropriate for bulbar urethral strictures under 2.5 cm in length. Re-approximation of longer strictures can result in curvature, pain and tension on the anastomosis. Overall, long-term success approaches 95 to 100 percent.

- Recurrence after EPA is due to inadequate removal of the fibrosis and inadequate urethral mobilization (where excess anastomotic tension results in deficient blood supply). For strictures longer than 2.5 cm, the surgeon can use appropriate techniques.

Grafts

General

- A graft is a tissue transfer that is dependent on the host blood supply for survival. The process is called a graft “take” and occurs in two stages, imbibition and inosculation.

- Imbibition is nutrient absorption from the host bed in the first 48 hours.

- The second phase is inosculation, which take place from 48 to 96 hours after grafting. Inosculation is graft revascularization by blood vessels and lymph joining from the host bed to the graft.

- Conditions for graft success are:

- Well-vascularized host bed

- Rapid onset of imbibition (passive diffusion of nutrients from the host bed)

- Immobilization of the graft

- Rapid onset of inosculation (in growth of blood vessels)

- Split-thickness skin graft comprises the epidermis (the outer, surface layer of skin) and the superficial section of the papillary dermis (thin upper layer of skin below the epidermis)

- Dermal graft comprises the deep papillary and the reticular dermis (a thicker layer of tissue found deep to the surface skin)

- Full-thickness skin graft involves all layers, the epidermis, papillary dermis and the reticular dermis.

Free-Graft Urethroplasty

- The primary grafts used are penile skin, buccal graft (mucosal [pink] lining of the cheeks) or outer layer of the bladder.

- Grafts are highly successful in the bulbar urethra as an onlay or patch technique and where a spongioplasty to cover the graft can be performed. Mucosa from the inner cheek is easy and quick to harvest, causes minimal sickness and has excellent take (up to 86 percent).

- Full-thickness skin grafts are used in urethral reconstruction because of their high “take,” and shrink little (15 to 25 percent). Split-thickness grafts are not to be used in one-stage urethroplasty because in unsupported tissue they can shrink as much as 50 percent. Penile skin should be avoided when the penile skin is not abundant or also affected by LSA.

- Grafts are particularly useful in the obese patient with a bulbar stricture, for whom time in surgical procedure needs to be minimized.

Meshed Graft Two-stage Urethroplasty

This is usually reserved for patients who have undergone failed urethroplasties or where the urethra and local skin are severely scarred. Two-stage reconstruction is also recommended when stricture is associated with a fistula or abscess, or lack of sufficient, well-vascularized local skin for a one-stage reconstruction.

Flaps

A flap is a tissue transfer where the donor blood supply is left intact. The success of a flap is described as “survival” and has better overall success than grafts.

Penile and Foreskin Island Flaps

- Penile flaps are the mainstay of urethral reconstruction.

- Penile skin flaps rely on the rich collateral blood supply within the tunica Dartos (the thin layer muscle fibers underlying the skin of the scrotum) for their survival.

- Island flaps are versatile and can be used in all areas of the anterior urethra. Success rates of 85 to 90 percent are achieved with onlay flaps where the urethral plate remains intact. Flaps that are completely rolled into a tube have nearly a 50 percent failure rate.

- Depending on the location and the length of the stricture, flaps may have to be developed in different positions and shapes.

Scrotal Skin Island Flaps

- Scrotal skin island flaps are used for bulbar strictures where time in surgery needs to be minimized or where other tissues are not available.

- When mobilizing a scrotal flap of skin, care should be taken to choose a non-hair bearing area. Otherwise, a hairy urethra can result and be complicated by recurrent infection, sprayed urinary stream and stone formation. A hairless patch of skin can often be found in the midline and the posterior scrotum.

- If the scrotum is hairy, the skin island can be expanded by hair removal. After the initial hair removal, the patient is reassessed six weeks later for a second treatment.

- The disadvantages of scrotal skin over penile skin are that it is more difficult to work with, tends to shrink and has a unilateral blood supply.

Combined Tissue Transfer

Occasionally, stricture length is so long that flap length is insufficient. In these cases, a combination of distal flap and proximal graft are used. Two island flaps also can be used. In doing so, extensive strictures can be reconstructed in a single stage, rather than the more traditional two-stage method.

Posterior Urethral Strictures

Urethral Distraction Injuries

Urethral distraction injuries occur in up to 10 percent of pelvic fractures and are mainly due to high-speed motor vehicle accidents and occupational injuries.

- Urethral strictures develop in nearly all patients after a complete urethral disruption. Initial management by primary realignment appears to decrease overall stricture incidence.

- Three to six months after initial injury, the prostate and bladder descend as the pelvic hematoma (clotted blood) is reabsorbed and organized.

- The eventual stricture length is commonly only 1 to 2 cm. Such relatively short strictures can be bridged easily by a one-stage urethroplasty.

- The stricture involves, to varying degrees, spongiofibrosis of the distal bulb and membranous urethra. The other potential segments of “stricture” are not true strictures of the urethra, but rather scar tissue in the intervening space between the dislocated prostate and the pelvic diaphragm.

- Less then 10 percent of urethral strictures are complex, that is, with long urethral defects (greater than 6 cm) or associated with anterior urethral strictures, rectal or bladder neck injury, fistulas (abnormal passages), or chronic cavities in tissues surrounding the urethra.

Stricture Evaluation

- Although newer imaging methods, including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been employed, dynamic fluoroscopic imaging with simultaneous voiding cystourethrography and retrograde urethrogram remains the gold standard. When fluoroscopic images are confusing, MRI is helpful in surgical planning.

- Before being considered for urethral reconstruction, the patient also must have:

- No evidence of pelvic abscess or infection

- A competent bladder neck. Since the external/membranous urethra is damaged, a competent bladder neck is essential to assure continence after reconstruction. A static cystogram followed by urinating can assess bladder neck function.

- No urethral instrumentation in the last three months (the scar must be stable).

Urethroplasty

- One-stage open urethroplasty is the gold standard for correcting posterior urethral strictures. Long-term success rates approach 90 to 95 percent. However, such surgery is technically demanding and time-consuming.

- Multiple minimally invasive techniques have been reported with most being some modification of the “cut to the light” procedure. Long-term results have been poor, and such techniques should be considered temporary measures and not methods for cure.

- Patients with anterior urethral strictures, hypospadias (an abnormality of the penis in which the urethra opens on the underside of the penis, instead of at the tip) or pelvis fracture where the blood supply to the penis and urethra are compromised. One-stage posterior urethroplasty is generally not recommended in such patients.

Post-Prostate Surgery Strictures

- Membranous urethral strictures occur in up to 6 percent of patients who undergo transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). The scar tissue is caused by the trauma of using too large a resectoscope/catheter or from overly aggressive distal prostate resection (removal of part of the prostate). After radical prostatectomy (total removal of the prostate), membranous urethral strictures are also rare and are the result of poor apposition of lining of the urethra and the lining of the bladder.

- TURP, simple prostatectomy and radical prostatectomy all damage the internal urethral sphincter and thus continence is subsequently dependent on the external striated sphincter.

- Strictures involving the external sphincter are best managed by urethral dilatation. Urethrotomy or other surgical repair often can result in incontinence.

Other Suggested Readings in the Medical Literature:

- Dixon CM, Hricak H, McAninch JW. Magnetic resonance imaging of traumatic posterior urethral defects and pelvic crush injuries. J Urol 148:1162, 1992.

- Morey AF, McAninch JW. Reconstruction of posterior urethral disruption injuries: Outcome analysis in 82 patients. J Urol 157:506, 1997.

- Orandi A. One-stage urethroplasty. Brit J Urol 40:717,1968.

- Pansadoro V, Emiliozzi P. Internal urethrotomy in the management of anterior urethral strictures: Long-term follow-up. J Urol 156:73, 1996.

- Quartey JKM. One-stage penile/preputial island flap urethroplasty for urethral stricture. J Urol 134:474, 1985.

- Schreiter F, Noll F. Mesh graft urethroplasty using a split-thickness skin graft of foreskin. J Urol 142:1223, 1989.

- Waterhouse K, Abrahms JI, Gruber H, et al. The transpubic approach to the lower urinary tract. J Urol 109:486, 1973.

- Webster GD. Management of complex posterior urethral strictures. Problems in Urology 1:226,1987.

- Webster GD, Koefoot RB, Sihelnik SA. Urethroplasty management in 200 cases of urethral stricture: A rationale for procedure selection. J Urol 134: 892,